By Marlen V. Ronquillo | October 18, 2014

THOSE who know about dates and chronology of events know too well that the genesis of the MRT 3’s slide to hell began in earnest in 2012. That was the year a group of LP operatives mostly from Pangasinan incorporated a cottage industry called PH-Trams with a vile but grand design – bag the lucrative operations and maintenance (O & M) contract of

the MRT 3.

It was just like contracting a quack clinic to fight the Ebola nightmare. But that did not matter. The LP flunkies knew that all handicaps of the cottage firm PH-Trams would be obscured by their LP affinity. The confidence was on firm ground. Several weeks after the incorporation of PH-Trams, it bagged the more than P500 million a year contract to operate and maintain the MRT 3.

There was a subsequent revelation that added stink to the sweetheart, lucrative deal bagged by PH-Trams: that the uncle of the wife of then LRTA Administrator Al Vitangcol 3rd was one of the incorporators. But what the heck. What was the LP in power for.

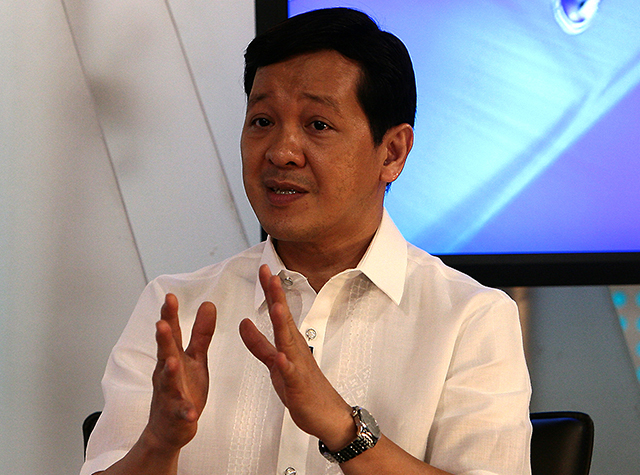

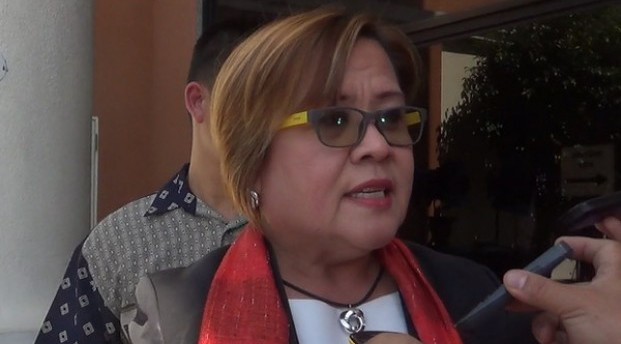

At a recent Senate hearing on why the MRT 3 is now one of the worst urban rail systems in the world, DOTC Secretary Joseph Abaya, one of the most powerful figures in the LP, skipped the part about the cronyism and corruption that led to awarding the contract to PH-Trams. He predictably spun the tall tale that Sumitomo of Japan was kicked out in favor of PH-Trams of the LP and Pangasinan because the former committed the following:

It asked for a higher O&M fee

It declined to back a new O&M contract with a financial warranty

It allegedly stole spare parts from MRT 3’s own trains which it later resold to MRT 3 as brand new.

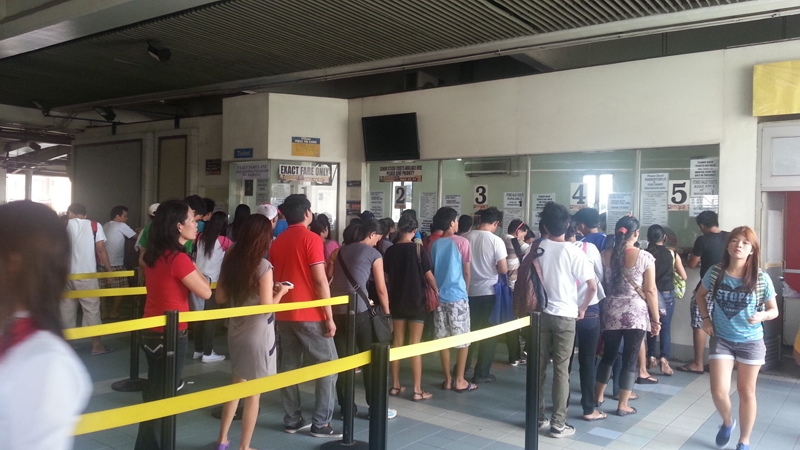

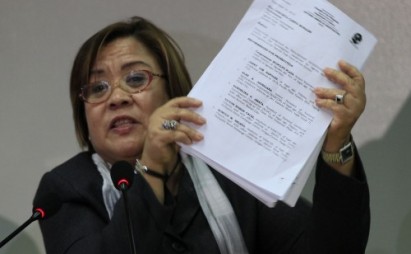

If true, the three were indeed serious breaches that were enough to blackball Sumitomo. In the same Senate hearing, Abaya’s charges were, however, refuted point by point. Sumitomo’s O&M contract had a financial warranty. The contract with PH-Trams was probably P450 million costlier than Sumitomo’s, according to a senator. More, Sumitomo, during its term at the MRT 3 guaranteed the operations of 20 trains and 40 coaches during peak operating hours, a commitment which it fulfilled until the DOTC and the LRTA schemed to scrap its contract in favor of cottage/crony firm PH – Trams.

Sumitomo’s contract had a general commitment called “single point of responsibility” which was embedded to ensure that a sufficient number of trains and coaches were operating safely and efficiently especially during peak hours. That commitment, according to private partners of the MRT 3, vanished from the O&M contract after the takeover of PH –Trams in 2012, and its just-as-incompetent successor in 2013, the other crony firm APT-Global.

Abaya also withheld from the senators these two relevant timelines. That cottage firm PH-Trams was awarded a multi-million contract barely a couple of months after its incorporation. And that Sumitomo was kicked out barely 12 days before its O&M contract ended in 2012. The irrational exuberance to throw out an established global company in favor of a crony firm was breathtaking in a negative way.

The O&M contracts to PH-Trams and APT-Global were structured, noted some senators, to make the MRT 3 fail and fail miserably. Note that the contract with Sumitomo placed the entire responsibility on Sumitomo: maintenance, service, overhauling and replacement of rails and parts, etc.

The PH-Trams and APT Global contracts were limited to maintenance. Vital work such as rail replacement and overhaul of trains and the provision of communication systems will be contracted out separately in an upcoming public biding. Currently, the DOTC is in charge of other vital work as it chopped the original total package of Sumitomo. In effect, the DOTC, by scrapping the contract of Sumitomo, made the O&M cost costlier by around P450 million a year, according to senators.

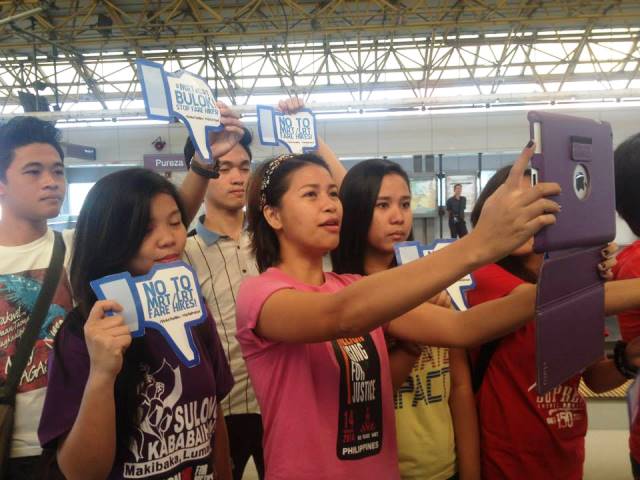

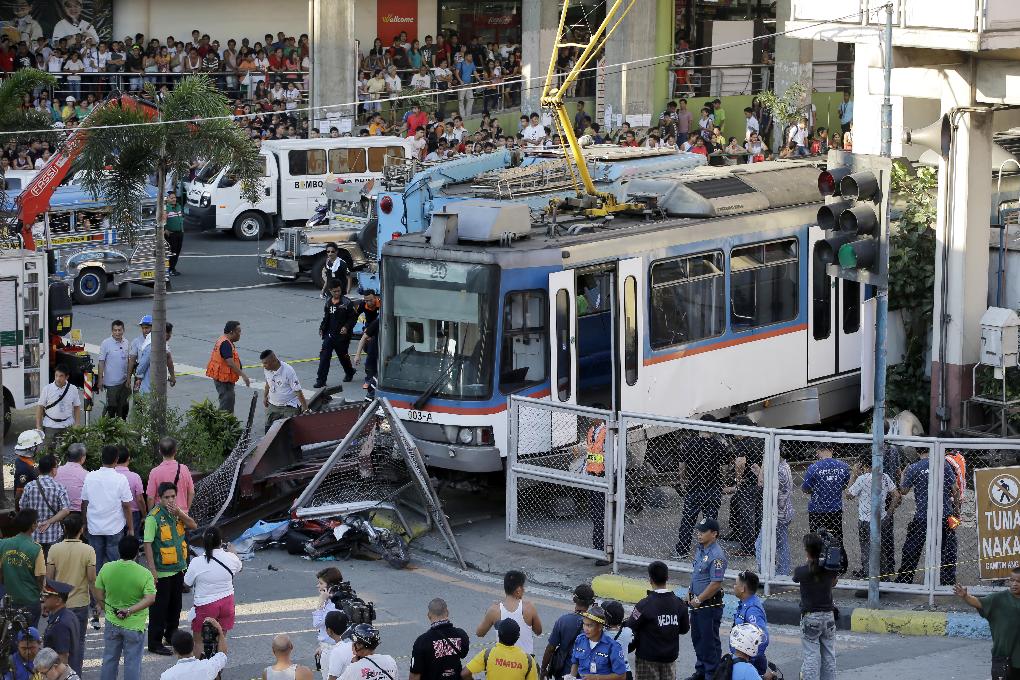

The structure of the post-Sumitomo contract was the reason cited by APT-Global in not accepting the responsibility for the spate of MRT 3 accidents, which totaled 17 after a disastrous overshoot of a train last August 13 that seriously injured 38 passengers. APT Global said its work was limited to maintenance so the DOTC should be asked to explain the engineering and communications breakdowns.

There was no single point of responsibility in the contract and the crony firm can bungle its job and get away with it.

The DOTC recently released a memo that confirmed Abaya’s worst nightmare – about the O&M contractor using cannibalized parts which are supplied back to the MRT 3 trains and passed off as brand-new. The problem was Sumitomo was not the culprit. It was the crony firm and current maintenance contractor APT-Global that was named in the DOTC memo.

The DOTC has misgivings about the crony firm. The crony firm has misgivings about the DOTC. But there would be no public fight, no public unloading of dirty laundry. The events and circumstances that led to the firing of Sumitomo and the contracting of PH-Trams and APT Global will be dirty enough to bring down several prominent figures in the LP and there would be no public revelation of those events and circumstances.

The focus of the DOTC right now is on two issues. Buy new trains and use P54 billion to buy the economic rights of two state-owned banks – Land Bank of the Philippines and Development Bank of the Philippines — in the MRT 3 under a so-called Equity Value Buyout (EVBO) scheme.

But as with the contracting of the PH-Trams and the APT-Global, both moves are contentious and fraught with legal issues. Can the DOTC and LRTA use government money to buy new trains for a rail company partly owned by private interests? The government cannot use public money that would directly benefit private interests, according to law. The EVBO will not change anything in the corporate structure as the private owners’ shares will not be settled.

In the Senate hearings, the sense of the senators was this. Use the P54 billion for priority projects. Better, get out of the MRT 3 and allow the private sector to run it without the heavy hand of the state.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook